En intressant idéhistorisk tendens de senaste decennierna har varit att den radikala högern, i synnerhet den med etno-nationalistiska förtecken, i många fall brutit med staten. Tidiga exempel på detta var nationalanarkisterna och ”högeranarkister” som Karl-Heinz Weissmann, idag har tendensen nått Sverige med Jonas Nilssons anarko-fascism som ett exempel. Egentligen är det en äldre trend, redan Hamsun företrädde åsikter som kunde beskrivas som nationalanarkistiska, Tolkien anarko-monarkistiska. Nietzsche beskrev den moderna staten som ett kallt monster. Staten framstår kort sagt för växande delar av högern inte längre som ett möjligt redskap att använda utan som en fiende. Detta för oss osökt över till frågan om den anarkistiska idétraditionen. Att både Proudhon, Bakunin och Landauer hade åsikter som idag skulle ses som politiskt inkorrekta är förmodligen ingen nyhet. En mycket intressant anarkist i sammanhanget är annars Pjotr Kropotkin, inte minst på grund av tankarna kring direkt aktion, summerad i orden ”act for yourselves”, och inbördes hjälp.

Kropotkin om germanerna

Far from acting with disregard to human life, the barbarians, moreover, knew nothing of the horrid punishments introduced at a later epoch by the laic and canonic laws under Roman and Byzantine influence. For, if the Saxon code admitted the death penalty rather freely even in cases of incendiarism and armed robbery, the other barbarian codes pronounced it exclusively in cases of betrayal of one’s kin, and sacrilege against the community’s gods, as the only means to appease the gods.

– Kropotkin om germanska straff

Kropotkin (1842-1921) var en av den tidiga anarkismens mer originella och spännande tänkare. Hans tankar kring värdet av att handla själv istället för att förlita sig på politiker är fortsatt givande oavsett var man befinner sig politiskt. Kropotkins intresse för inbördes hjälp är också värdefullt, oavsett om man kallar sig klassisk liberal, identitär eller socialist. Det påminner oss om att våra förfäders samhälle hade inslag inte bara av stat och konkurrens, utan också inbördes hjälp. Han skildrade detta i boken Mutual aid.

Eftersom han även var geograf och zoolog, kunde Kropotkin modifiera den mer vulgära darwinismen, och påvisa hur inbördes hjälp och samarbete var en viktig faktor i evolutionen. Med moderna termer kan man säga att han hade ett sociobiologiskt perspektiv, men att det utmynnade i anarkism och kommunism istället för i socialdarwinism eller fascism. Värt att notera är att mer sentida forskning gett Kropotkin rätt, samarbete spelar en viktig roll inte minst då mycket av det naturliga urvalet äger rum på gruppnivå. Det är i förbigående sagt därför atomiseringen är ett sådant problem, dels strider det mot vår natur eller artväsen, dels försvagar det vår grupp.

Kropotkins zoologiska perspektiv gjorde att han kunde hitta många exempel på inbördes hjälp i naturen. Men geografen Kropotkin hittade också många exempel i mänskliga samhällen från olika delar av världen. Av särskilt intresse är styckena om inbördes hjälp hos germanerna och den medeltida skrå- och gilleorganisationen. Om germanerna skrev Kropotkin positivt. Han såg med avsky på statens brutala bestraffningar, på tortyr och liknande, och jämförde med germanerna. Han citerade George Dasents positiva summering av nordmannens kvaliteter:

To do what lay before him openly and like a man, without fear of either foes, fiends, or fate;… to be free and daring in all his deeds; to be gentle and generous to his friends and kinsmen; to be stern and grim to his foes [those who are under the lex talionis], but even towards them to fulfil all bounden duties…. To be no truce-breaker, nor tale-bearer, nor backbiter. To utter nothing against any man that he would not dare to tell him to his face. To turn no man from his door who sought food or shelter, even though he were a foe. The same or still better principles permeate the Welsh epic poetry and triads. To act ”according to the nature of mildness and the principles of equity,” without regard to the foes or to the friends, and ”to repair the wrong,” are the highest duties of man; ”evil is death, good is life,” exclaims the poet legislator. ”The World would be fool, if agreements made on lips were not honourable” — the Brehon law says.

Liknande människoideal identifierade han även hos andra ”barbariska” folk (bland annat tar han upp kabylerna och deras samarbete i cof). Intressant är att Kropotkin också berörde krigarförbund som ett uttryck för inbördes hjälp. Vi har här att göra med varianter av mannaförbundet. Han beskrev stammar och folk som föredrog fred framför krig, men som överlät krigets värv åt grupper av män:

…they left the uncertain warlike pursuits to brotherhoods, scholae, or ”trusts” of unruly men, gathered round temporary chieftains, who wandered about, offering their adventurous spirit, their arms, and their knowledge of warfare for the protection of populations, only too anxious to be left in peace. The warrior bands came and went, prosecuting their family feuds; but the great mass continued to till the soil, taking but little notice of their would-be rulers, so long as they did not interfere with the independence of their village communities.

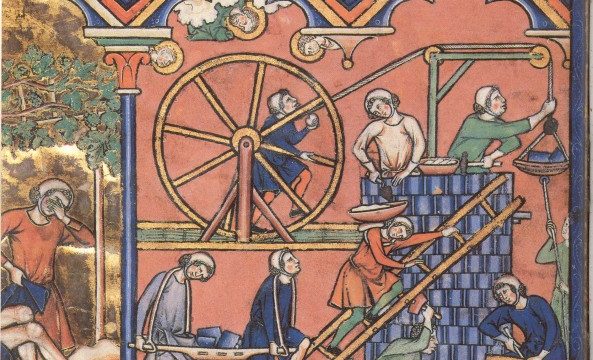

Gillen och skrån

Such were the leading ideas of those brotherhoods which gradually covered the whole of medieval life. In fact, we know of guilds among all possible professions: guilds of serfs, guilds of freemen, and guilds of both serfs and freemen; guilds called into life for the special purpose of hunting, fishing, or a trading expedition, and dissolved when the special purpose had been achieved; and guilds lasting for centuries in a given craft or trade. And, in proportion as life took an always greater variety of pursuits, the variety in the guilds grew in proportion. So we see not only merchants, craftsmen, hunters, and peasants united in guilds; we also see guilds of priests, painters, teachers of primary schools and universities, guilds for performing the passion play, for building a church, for developing the ”mystery” of a given school of art or craft, or for a special recreation — even guilds among beggars, executioners, and lost women, all organized on the same double principle of self-jurisdiction and mutual support. For Russia we have positive evidence showing that the very ”making of Russia” was as much the work of its hunters’, fishermen’s, and traders’ artels as of the budding village communities, and up to the present day the country is covered with artels.

– Kropotkin

Det medeltida Europa var på samma gång frihetligt och gemenskapande, med drag som kan tilltala anarkisten och traditionalisten. Det knöts samman av en väv av gillen, munk- och nunneordnar, feodala lojaliteter och bygemenskaper. Gille- och skråordningen har inspirerat samhällsfilosofer in i modern tid, exempelvis Karl Marlo, Arthur Penty och von Gierke. Även Kropotkin beskrev den som ett uttryck för inbördes hjälp. Det etos som genomsyrade gillen och skrån var föredömligt. Medlemmarna skulle behandla, och kalla, varandra som bröder och systrar. De ägde en del gemensamt (boskap, mark, byggnader, helgedomar). De skulle hjälpa varandra i konflikter med utomstående men undvika konflikter med varandra. Kropotkin tar ett danskt gille som exempel:

Taking, for instance, the skraa of some early Danish guild, we read in it, first, a statement of the general brotherly feelings which must reign in the guild; next come the regulations relative to self-jurisdiction in cases of quarrels arising between two brothers, or a brother and a stranger; and then, the social duties of the brethren are enumerated. If a brother’s house is burned, or he has lost his ship, or has suffered on a pilgrim’s voyage, all the brethren must come to his aid. If a brother falls dangerously ill, two brethren must keep watch by his bed till he is out of danger, and if he dies, the brethren must bury him — a great affair in those times of pestilences — and follow him to the church and the grave. After his death they must provide for his children, if necessary; very often the widow becomes a sister to the guild.

Sammantaget är det en inspirerande beskrivning av en samhälls- och organisationsmodell Kropotkin ger. När den moderna staten tappar mark finns det mycket av värde i medeltidens gillen och skrån, i kombinationen av frivillighet, autonomi och gemenskap.