Det finns sedan tidigt 1900-tal en återkommande koppling mellan europeisk radikalhöger, särskilt sådan med hedniska förtecken, och den mithraism som konkurrerade med den tidiga kristendomen om att bli romersk statsreligion. Den italienske traditionalisten Julius Evola återkom till mithraismen både under tiden i den ockulta UR-gruppen och i ett antal kortare artiklar. Den nordamerikanske skribenten och musikern Michael Moynihan har i sitt projekt Blood Axis odödliggjort Kiplings A Song to Mithras. Denna koppling är naturlig, då Mithraskulten å ena sidan saknade vissa av de inslag bland annat Evola kritiserade hos den tidiga kristendomen, och å andra sidan representerar en imperiell hedendom, en kult för aristokrater och legionärer.

En klassisk studie av Mithraskulten är Franz Cumonts The Mysteries of Mithra, som finns tillgänglig på Sacred Texts.com. Trots sin ålder och trots Cumonts personliga åsikter ger den en lättillgänglig introduktion till mysterierna. Man kan notera att Cumont gör en distinktion mellan Öst och Väst, och associerar Mithras med negativt östligt inflytande under Roms höst. Det gemensamma indo-europeiska ursprunget till både Mithras och Rom spelar för honom en mindre roll.

In the Avesta, Mithra is the genius of the celestial light. He appears before sunrise on the rocky summits of the mountains; during the day he traverses the wide firmament in his chariot drawn by four white horses, and when night falls he still illumines with flickering glow the surface of the earth, ”ever waking, ever watchful.”… by a natural transition he became for ethics the god of truth and integrity, the one that was invoked in solemn oaths, that pledged the fulfilment of contracts, that punished perjurers… His is the beneficent genius that accords peace of conscience, wisdom, and honor along with prosperity, and causes harmony to reign among all his votaries… He combats unceasingly the spirits of evil; and the iniquitous that serve them feel also the terrible visitations of his wrath. From his celestial eyrie he spies out his enemies; armed in fullest panoply he swoops down upon them, scatters and slaughters them. He desolates and lays waste the homes of the wicked, he annihilates the tribes and the nations that are hostile to him. On the other hand he is the puissant ally of the faithful in their warlike expeditions.

– Cumont

Cumont identifierar Mithras ursprung i indo-iransk tradition, vilken sedan påverkats av babylonisk astrologi och lokala kulter. Resultatet var en synkretisk världsåskådning, där lokala gudar kunde förknippas med mithraismens gestalter. På så vis hade den varit en lämplig statskult i det romerska imperiet (så kunde exempelvis keltiska gudar kopplas till lämpliga figurer i Mithras kosmogoni, liksom de grekiska gudarna, inklusive dioscuri).

Cumont följer hur denna ursprungligen persiska kult spreds i Rom, främst genom soldater och slavar från de östliga provinserna. I likhet med den tidiga kristendomen var det ursprungligen en folklig religion, men mithraismen nådde snart aristokratin och kejsarna. Detta förklarar Cumont med mithraismens inställning till kungar. Till skillnad från en del östliga kulter betraktade den inte kungar som levande gudar, däremot hade goda härskare en särskild relation till det gudomliga. Cumonts beskrivning av denna relation, och av hvareno, för tankarna till indo-europeiska föreställningar om sådant som segerns metafysiska betydelse.

The Persians, like the Egyptians, prostrated themselves before their sovereigns, but they nevertheless did not regard them as gods. When they rendered homage to the ”demon” of their king, as they did at Rome to the ”genius” of Cæsar (genius Cæsaris), they worshipped only the divine element that resided in every man and formed part of his soul. The majesty of the monarchs was sacred solely because it descended to them from Ahura-Mazda, whose divine wish had placed them on their throne. They ruled ”by the grace” of the creator of heaven and earth. The Iranians pictured this ”grace” as a sort of supernatural fire as a dazzling aureole, or nimbus of ”glory,” which belonged especially to the gods, but which also shed its radiance upon princes and consecrated their power. The Hvarenô, as the Avesta calls it, illuminated legitimate sovereigns and withdrew its light from usurpers as from impious persons, who were soon destined to lose, along with its possession, both their crowns and their lives. On the other hand, those who were deserving of obtaining and protecting it received as their reward unceasing prosperity, great fame, and perpetual victory over their enemies.

– Cumont

Kejsaren kopplades här till Solen, Cumont skriver:

In assuming the surname invictus (invincible), the Cæsars formally announced the intimate alliance which they had contracted with the Sun, and they tended more and more to emphasize their likeness to him. The same reason induced them to assume the still more ambitious epithet of ”eternal,” which, having long been employed in ordinary usage, was in the third century finally introduced into the official formularies. This epithet, like the first, is borne especially by the solar divinities of the Orient, the worship of whom spread in Italy at the beginning of our era. Applied to the sovereigns, it reveals more clearly than the first-named epithet the conviction that from their intimate companionship with the Sun they were united to him by an actual identity of nature.

Ett idékomplex där egenskaper som Solen, legitimt styre, framgång, inre oantastlighet, sanning, oövervinnerlighet och evighet hänger intimt samman framträder här, med tydliga kopplingar till den hyperboreanska tradition bland annat Evola beskrivit.

Cumont tar också upp sådant som tjuroffret, de olika graderna i mysterierna, och konflikten med de kristna. Han menar att en svaghet i mithraismen var att den inte hade plats för kvinnor, däremot ingick den en allians med Magna Materkulten. Det fanns annars betydande likheter mellan Kristus och Mithras. Sammantaget är Cumonts bok en intressant beskrivning av en religion som nästan blev romersk statskult, med de positiva följder det hade haft för religiös kontinuitet i imperiet.

Relaterat

Dumezil och Destiny of a King

Gangleri – Some information on mithraism

Julius Evola och Mithras

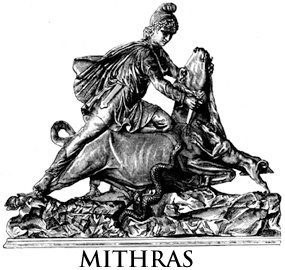

Mithraskulten